StrobeLite:

Jittery Reflections from the Brookings InstitutionON Tuesday, August 19, 2003 at 11:00 AM, Strobe Talbott,

President of the Brookings Institution participated in an online chat with the Washington

Post. IRmep, which has published a great deal lately about American think tanks in

general and Middle East think tanks in particular, was not invited, but provides annotated

comments to our readers that help explain the crisis of credibility now engulfing

Brookings and other formerly vaunted American think tanks.

Transcript

Politics: The Brookings Institution

Strobe Talbott

Brookings Institution President

Tuesday, August 19, 2003; 11:00 AM

The transcript and IRmep data and analysis in Bold follows.

Strobe Talbott: I'm delighted to have a chance to join in a

discussion with your Web-users. As a former journalist who frequents cyberspace, it's fun

to see the way the Post is taking advantage of the medium....

College Park, Md.: Who are the main funders of Brookings, and

how does that impact your choices of topics to study and the outcomes you advocate?

Strobe Talbott: Brookings gets its funding from a combination

of sources. We have an endowment, which covers about a quarter of our 40 million dollar a

year budget; the rest comes from foundations, corporations and individuals....

IRmep: Brookings has immense resources available for

research, advocacy, and lobbying. In 2000, Brookings reported just under a quarter

of a billion dollars in assets ($242,176,802) to the Internal Revenue Service.

With its current financial resources and expenditures, Brookings could be completely self

sufficient from any further donations.

However, donations continue to pour in.

No one funds research without a motive. The

resources of those still funding Brookings and the centers to which they contribute is an

all-important question that Brookings, and most other think tanks, simply refuse to

answer.

Washington, D.C.: What is your best response to individuals

who assert that think tanks are of limited practical value, but rather produce thoughts or

rather lines of thinking that are highly esoteric and disassociated from actual real life

situations and social needs?

Strobe Talbott: There are obviously lots of different think

tanks -- more than a hundred just in Washington -- and different kinds as well. Brookings

has, for its more than 80 years in existence, made a specialty out of research that is of

use and interest to policymakers, and also to informing the public about policy issues. In

short, we put a premium on relevance.

IRmep: This is a question of perspective.

Esoteric and disconnected is not an accurate description of Brookings policy

promotion. Brookings enjoys privileged access to policy makers and key government

officials, without the need for filing as a lobby, foreign agent, or special interest

group. It is precisely this level of access and ability to influence policymakers

from behind the scenes that makes Brookings an excellent investment for some vested

interests. The only group that legitimately considers Brookings to be esoteric and

disassociated is average Americans.

Arlington, Va.: Why do you think people have different views

and opinions? How does you institute try to influence and persuade others?

Also, is there an objective analysis versus politically influenced

analysis? For example do you think any one or any agency could have produced an object

analysis on Iraq that is not politically motivated one way or the other?

Strobe Talbott: It's healthy and natural that there should be

a wide range of views on Think Tank Row, just as there is in the country at large. In

fact, we encourage a diversity of views here at Brookings. Our ability to influence the

public and the policymaking community derives not just from the expertise of our scholars

but from the fact that they are truly independent and nonpartisan -- that is, they're not

advancing a political party's agenda.

Iraq is a good example of this. Our scholars who know a lot about that subject -- and

there are quite a few -- had some points on which they supported the premise of the

administration's policy, other points where they had their differences.

IRmep: Brookings, like most fellow think tanks and

immediate neighbors on Dupont Circle in Washington D.C. contributed relatively little to

what would be considered "honest debate" on the Iraq question. A content

analysis of Brookings press quotes reveals that issues of low to no relevance at Brookings

were the likely costs of postwar occupation, implications for U.S. credibility if WMD

intelligence was flawed, and the new era that would be created by a democracy launching a

"preemptive" war the rest of the world protested. Similarly

irrelevant to Brookings were the conflict's impact on trade, regional economic development

and other issues affecting the U.S. economy.

Parkville, Md.: The Brookings Institute is often cited as a

Democratic counterpart to right-wing think tanks such as the Heritage Foundation and the

American Enterprise Institute. Many Democrats, however, disagree and have gone about

putting together a American Majority Institute, to serve as a counterweight to Heritage

and AEI.

My question is this: How would you contrast Brookings with AEI and

Heritage, and what advice would you give Democrats in setting up a more unabashedly

partisan think tank of their very own?

Strobe Talbott: The key word in describing Brookings is

nonpartisan. That, by the way, is different from "bipartisan." Our Congress is,

or should be, bipartisan in that it looks for common ground between the two parties. A

nonpartisan approach is one that is open to the possibility that neither party has the

right answer to a tough issue. At Brookings, we have people who are registered

Republicans, Democrats and Independents. We have an environment here that is open and

collegial. People listen to each other and think about alternative views in shaping their

own. We have had people who come to Brookings from Republican administrations (for

example, Ken Dam, who was deputy treasury secretary, and it was recently announced that

Larry Thompson, the deputy attorney general, will be coming here next month), as well as

from Democratic administrations. An example there, in addition to myself, is Jim

Steinberg, the head of our foreign policy department. His predecessor, Richard Haass, went

from Brookings into the Bush administration as director of policy planning -- a job Jim

had held before. So there's a revolving door that ensures maximum nonpartisanship, at

least at this outfit.

IRmep: From a systems analysis perspective, the think tank

ecosystem does not at all favor progressive or liberal thought. Since conservative

principles are generally broadly agreed upon, with an anchor in the past, think tanks can,

and often do, tacitly agree on general principles.

Liberals, however, generally only agree on the need for

change. Any three liberals gathered among the fluted columns and polished marble

floors of a new think tank would likely profoundly disagree on approaches for changing and

improving America. Thus, truly progressive and liberal thinkers will for ever be

found scattered about in colleges and universities.

West Palm Beach, Fla.: Dear Strobe: Brookings is considered

to be the moderate to left think tank as compared to the libertarian Cato or

right/conservative American Enterprise Institute or Hudson, or the conservative Heritage

Foundation, etc. Is there any updated score card or chart that arrays/arranges think tanks

based on their bias/point of view and perspective. Please don't say you are "fair and

balanced" or I'll report you to Fox News Network and you will become a co-defendant

with Al Franken.

Strobe Talbott: Okay, I'll rise to the bait! We're fair and

balanced. Take a look at our mission statement. And more to the point, take a look at our

product, which comes in the form of books, op-eds, "policy briefs," appearances

by our scholars in the media -- and you'll see that they are not advancing any party

agenda and that, because they reach their conclusions through open-minded inquiry and

rigorous analysis, they often surprise people who mistakenly associate us with a fixed

point on the political spectrum (sometimes they even surprise themselves).

IRmep: Brookings is the single most influential think

tank in the U.S. if measured by number of media citations. Brookings provided 17% of

the media quotes from the 25 think tanks profiled in a year 2002 Nexis search conducted by

FAIR. When ranked by media quotes, Brookings emerges as the most important

opinion leading think tank in America.

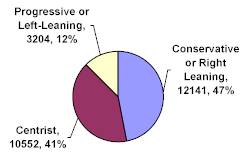

Exhibit 1 Citations of Think Tanks in Media

(Source: FAIR and IRmep 2003)

However, the output of policy analysis at Brookings differs little from that of

conservative think tanks. 47% of total quotations from think tanks are Conservative

or right leaning, 41% are Centrist, and only 12% are considered Progressive or left

leaning. Brookings does little that is unique in the way of media influence that

could be called "fair and balanced" much less "Progressive".

Exhibit 2 Number of Media Citations by Ideaology

(Source: FAIR and IRmep 2003)

Brussels, Belgium: Mr. Talbott,

Europeans liked (loved!) Clinton but can't stomach Bush. Why? The Clinton Administration

also used U.S. forces to affect regime change and, arguably, Bush follows the same foreign

policy objectives: securing U.S. interests, fighting terror, promoting democracy, engaging

allied forces in peace-making operations, etc.

What did Bush do that so alienates Europeans (or, what did Clinton

do to endear himself so to Europeans?) There is more to this than Kyoto and Iraq, but

what? (Not the Saxophone!?)

Strobe Talbott: Actually, the situation is more complicated

than you suggest. As someone who worked in the Clinton administration, I can assure you

that there was plenty of complaint abroad, particularly in Europe, about American

"unilateralism" from time to time. The French Foreign Minister, Hubert Vedrine,

called the US "l'hyperpussiance" -- the hyperpower -- and he didn't mean it as a

compliment. In fact, Vedrine elaborated on this theme at a conference here at Brookings.

The comment was directed at the Clinton administration. As for the Bush administration,

there's no question that transatlantic relations have gone through a bad patch, but that

was at least in part because of the way President Chirac of France made it hard if not

impossible for the Bush administration to keep the UN involved in the endgame on Iraq. I

think there's a real effort underway, on both sides of the Atlantic, to smooth things

over.

IRmep: As Strobe correctly states, since there was an

"endgame" as opposed to any actual consultation, high level negotiation or

debate between the administration and key U.S. allies, the U.S. was unable to put together

a coalition in the rush to war. To American Enterprise Institute and Brookings, the

lack of ally malleability means either that new allies are necessary, that NGOs are

obsolete, or that new ways of coercing traditional allies are needed. Most

legitimate observers understand that treatment of longtime allies that are globally

sophisticated does not involve a predetermined "endgame" but rather strategic

cooperation through honest debate.

New York, N.Y.: What issues do you see driving the 2004

election?

Strobe Talbott: Brookings has just published an important

book called "Agenda for the Nation," which provides very useful, thoughtful

readable analysis on many of the big issues for next year: the budget (including tax

policy), homeland security and the direction of national defense post-9/11, welfare

reform, international trade in an era of globalization.... Economics, as you may know, was

the original franchise of Brookings back nearly a century ago, and it's remained a key

part of what we do, but we also now have full programs on the state of our cities, on

foreign policy and on ways to improve our governing institutions. You can be sure that

Brookings will, starting in about two weeks, have a full array of programs that are

intended to help citizens understand the issues of the presidential campaign.

Alexandria, Va.: One of the objections raised against Bush

nominee Daniel Pipes is that he runs a Web site called Campus Watch that in the past has

criticized professors for what those professors taught and said.

Do you have any problem with anyone criticizing Brookings

Institution staff for what those staff members have taught or said? (Assuming, of course,

that the criticisms are not libelous.)

Strobe Talbott: In general, my colleagues are not against

criticism. It's a component of a healthy national debate. We engage in criticism

ourselves, although we try hard (and I think successfully) to keep it from being ad

hominem or partisan -- i.e., we try to make it constructive. I do have strong reservations

about what I'd call "attack research" and any sort of criticism that labels as

unpatriotic questions raised about ANY administration's policies.

IRmep: The Campus Watch website is a relevant metaphor

for the larger battle between think tanks and academia. While Campus Watch is overt in

discrediting political views it disagrees with, and then attempting to derail university

funding (such as title VI funds) in Congress, other think tanks are doing essentially the

same thing.

By employing powerful PR agencies to dominate highly limited prime time slots on

national television, think tanks have edged academics out of many key discussions.

By replacing real scholars with ideologues, the national debate has suffered

greatly. No better example exists than the broadcast punditry and one sided analysis

during the run-up to the invasion of Iraq.

Brookings and other think tanks generally fear deep analysis

of the background of their analysts (ad hominem). The ties to special interest

lobbies, foreign governments, and well established political movements clearly influences

policy output to a level that most strive to focus on any issue but authorship.

Harrisburg, Pa.: What is your analysis of how the Russian

government is doing? Is the economy improving any? Have the possibilities of communists

regaining power diminished significantly?

Strobe Talbott: Russia has made extraordinary strides in the

last decade and a half. As someone who has spent most of his career studying that place, I

never expected to see the day when Russia would be developing a parliamentary democracy

and a multi-party political system. That said, there are a lot of problems, including in

the economy. The Russian economy was beginning to turn around and even take off, but the

recent showdown between some powers-that-be in the Kremlin and the so-called oligarchs has

had a chilling effect on Russia's ability to attract and retain foreign capital, which is

crucial if the economy is going to continue to modernize.

My other big concern about Russia is Chechnya, which is festering in a way that threatens

to poison the democratization of the country as a whole.

Washington, D.C.: How would you characterize the differences

between think tanks and university research/institutes/centers? For think tanks, other

than providing a convenient base for career political/policy people and intellectuals in

between jobs/administrations, isn't there a great deal of overlap, and don't academic

enterprises hold out prospect of even greater objectivity because most academicians are

not looking for government/party jobs after the next election cycle?

Strobe Talbott: I respect the work done in universities, and

spent a year at Yale between my stint in gov't and coming here to Brookings. Many of our

scholars have been university professors and quite a few still teach at universities in

the DC area (Georgetown, Johns Hopkins, U of Maryland, George Mason, etc.) But one

difference between a think tank and a university is that we do not go in much for

"pure" research -- which is to say, we emphasize research that is relevant and

useful to policymakers. I don't think our objectivity is jeopardized by our

policy-orientation. Quite the contrary, we make a real effort to keep our policy objective

in the sense that we let chips fall where they may as we identify the big questions and

seek the big answers -- rather than letting our product be skewed in any fashion by

ideological or partisan preferences.

IRmep: Academia may be the last bastion of free thinking and

honest debate about public policy. Since the role of think tank pundits is

ultimately to advocate, rather than find the truth, America is replacing diamonds forged

in the crucible of debate, with spin produced in self referential and deeply compromised

"black boxes."

Washington, D.C.: Brookings is fair and balanced. That's the

problem. There's nothing in the center/left that takes as aggressive an approach to

changing the national debate and influencing policymakers the way the Right-wing think

tanks do. Why doesn't the left have similar institutions?

Strobe Talbott: I don't think what you've identified is

entirely accurate, nor is it necessarily a problem. There are think tanks that

affirmatively identify themselves with liberal (or "progressive") positions. As

you know, there's an effort underway right now to set up a new one -- quite explicitly as

a counterbalance to those on the conservative end of the spectrum. My own view is that

there is now more than ever -- in a supercharged atmosphere where there is a lot of

political polarization -- the need for an outfit like Brookings that seeks "fair and

balanced" answers to questions that should not be oversimplified or hijacked by one

side or the other.

Dallas, Tex.: Please comment on this administrations policy

towards Africa.

Thanks!

Strobe Talbott: It's good that President Bush went to Africa,

but it's too bad that that continent so often falls off the radar screen of American

foreign policy. That's been a historic problem, not just a current one. We have, among our

senior fellows, Susan Rice, who's doing some important work on corporate social

responsibility and globalization, but who is expert and experienced in Africa, having been

assistant secretary of state for that region, and we have a growing program on global

governance issues that is focusing a lot of on Africa. We also have, thanks to a generous

grant from Richard Blum of San Francisco, a "global poverty reduction

initiative" that has already come up with ideas on how best to spend the

administration's "Millennium Challenge Account" for foreign aid -- and Africa is

clearly one of the target beneficiaries of administration policy and the Brookings effort

to suggest ways that policy can be most effective.

Virginia: I looked over your staff roster, and most have

PhDs. What about the retired military man with only a high school degree but with 20 years

of war and operational experiences? Can they work there too?

Strobe Talbott: Great question! And you're addressing to

someone who does NOT have a Ph.D. One of the advantages of being an institution with more

than 50 resident scholars and nearly a 100 if you count non-resident affiliates is that we

can have many kinds of diversity, including in credentials and background. That way we can

have "true" academics, with their doctorates and university backgrounds, working

with "policy practitioners." As for military people, we have an Federal

Executive Fellows program that brings up-and-coming military and intelligence officers to

Brookings for year. They make a big contribution to our thinking and our writing, and they

feel it benefits them as they go back to the Pentagon or the intelligence community.

Somewhere, USA: If my figures are correct, you have been

president of The Brookings Institution for roughly a year now. How do you like your job?

What is your day to day routine?

Strobe Talbott: I love my job. One of the things I love about

it is that there's nothing routine about it. I have a chance to work with the scholars on

substance (I'm writing a book about India, Pakistan and nuclear weapons which brings me

into contact with our world-class South Asia expert, Steve Cohen), and it also gives me a

chance to work with the program directors and scholars on making sure that Brookings, when

it enters its second century in 2016 is as strong and as relevant as ever.

Arlington, Va.: What is the history of think tanks in the

United States? How did they start? Are there similar groups in countries overseas?

Strobe Talbott: Think tanks are in some ways not just an

American invention -- they're really still a uniquely American institution. There are

approximations of think tanks in other countries, but they tend by and large to be

sponsored by governments, by political parties, or offshoots of universities. My

colleagues and I here are looking into the possibility of helping partner-institutions in

other countries "clone" the Brookings model, which I see as a major opportunity

and responsibility for Brookings as the originator of that model.

IRmep: Brookings receives significant funding from the US

government. In 2000, Brookings received $1,169,524 million directly from the U.S.

government. This is 7% of the combined support given directly by the government and

individual contributors able to support their own policy agendas through a tax deductible

charitable contribution.

However, the idea of a "Brookings" model in a

smaller, or undeveloped country is curious. The 1980's and 1990's saw the formation

of many developed country institutions, such as stock markets, in regions that were

significantly different than the U.S. or Europe. Most failed. Since few developing

countries actually need to "sell" and promote policy initiatives, the utility of

a think tank is questionable while their absence is understandable.

Iowa: Any thoughts on the breaking news out of Baghdad? What

are your thoughts on the administration's policies in Iraq?

Strobe Talbott: The continuing violence, including today's

and the earlier bombing of the pipeline, shows that while Saddam is down (and let's hope

out) and Iraqis are vastly freer than they've been for decades, there is a nasty guerrilla

war of attrition underway. I refer you to the day-in-and-day-out good work being done by

our Saban Center for Middle East Policy, which has really dominated the think tank world's

commentary and analysis on Iraq. You'll see in the Center's work some big-picture

explanations of why the post-war has been in some ways more difficult than the war itself.

A crucial question is whether the Bush administration, having gone into Iraq without the

UN, will now be able to bring the UN -- and key regional countries like India -- into the

stabilization and reconstruction phase now underway.

IRmep: The Saban Center for Middle East Policy is

a microcosm for everything that is wrong with most U.S. Middle East policy think tanks.

The Center was created by a $13 million dollar contribution from a single donor, Fox

television executive Haim Saban to "promote effective US policies in the Middle

East". Saban also funded a center for the study of the American political

system in Israel.

The Saban Center would not even qualify for non-profit status were it not connected

with the larger Brookings Institution. The center is directed by Martin Indyk, a former

AIPAC lobbyist who both obtained U.S. citizenship and was later stripped of security

clearances under highly questionable circumstances. If the fate of American influence

in the Middle East depends on thinking from centers like Saban, we are in very deep

trouble.

Germany: Mr. Talbott, in your opinion, what should the

governments of Europe (old or new) do to help the U.S. forces in Iraq? By the way, my

impression (my view from Germany) is that between Europe and the White House there is no

discussion about this important issue. In the media Foreign Minister Joschka Fischer says

that Germany will not take part in any action in Iraq under any circumstances. What do you

think when you read about this?

Strobe Talbott: The distinction between "old" and

"new" Europe is somewhat misleading, but there's some truth to the perception

that the countries emerging from the old Soviet empire are more supportive of US policy

than our traditional allies in Western Europe. We have a Center on the US and France,

which is increasingly broadening its scope to include Europe as a whole, and if you check

that part of our Website, you'll see that the Center has conducted some conferences on the

issue you raise. Bottom-line, insofar as the Bush administration is prepared to involve

the UN in Iraq, the Europeans (old and new) will do more to help.

Bowie, Md.: Since conservatism is more amenable to people

with money than is liberalism, what kind of barrier is it to the promotion of liberal

ideas that conservatives can raise more money?

Strobe Talbott: My impression is that there is a lot of

"liberal" money that is, or will be, going to self-avowedly liberal think tanks.

Brookings is not in that category. Fortunately, there are a lot of donors who value what

Brookings does, which is independent and nonpartisan. We think that research and outreach

of that kind are in fact the best antidote to excessive partisanship.

IRmep: "Liberal" money tends to gravitate toward

relief oriented charities and more prestigious thought factories called

"colleges" and "universities". It is unlikely that any

progressive think tank will ever emerge given the structural limitations of think tanks.

Somewhere, USA: The earlier poster led me to another

question: what is the history of the Brookings? Have the institution's positions changed

from one president to another?

Strobe Talbott: Brookings was founded in 1916 by a wealthy

industrialist from St Louis named Robert S. Brookings. He came to Washington to help

Woodrow Wilson in the World War I effort and to inject what were then modern management

and account techniques into the running of the US government. Over time, Brookings

expanded its agenda to foreign policy and what we now call "governance studies."

I've been reading over the weekend a new book by Steven Schlesinger on the origins of the

UN. A Brookings economist, Leo Pasvolsky, was instrumental in that process. My

predecessors as president have seen it as their principal job to uphold the Institution's

independence and nonpartisanship, along with the highest standards of scholarship. That's

my job too, along with making sure that Brookings does change with the times and remains

on the cutting edge of thinking about the 21st century challenges for the US.

Gullsgate, Minn.: Strobe Talbott: I would assume that all

successful think tanks need considerable funds to maintain their institutions -- and

corporate funds that support those think tanks -- often define the interests of those

corporations. Or at least among the ultra conservative foundations. Or if not, how else

does an honorable or well intentioned think tank survive?

Strobe Talbott: You ask an important question. While we seek

and are grateful for corporate funding, we are assiduous about NOT letting our funders

influence the scholarly process whereby we come up with answers to the questions of the

day. Our corporate sponsors understand and support that principle. In that respect, there

are similarities to universities. Intellectual freedom is a key part of what makes

Brookings able to attract and retain the best talent -- and it's key to preserving our

reputation for producing objective, constructive, independent analysis.

IRmep: Brookings hasn't actually erected a so-called

"glass wall" between funders and researchers, any more than other research

institutions. A quick analysis of Saban center policy, and the background of its

funder and director, reveals little in the way of objectivity.

Wall Street's recent crisis of stock analyst credibility demonstrated the costs inflicted

upon the public of this type of highly compromised research. During the telecom

boom, analysts from Jack Grubman to dot-com experts newly minted from Forrester and

Jupiter Research filled the airwaves with insight and analysis the news media couldn't get

enough of.

And them came the big crash.

Iraq, for many think tanks, is now the equivalent of the

dot-com blowout. What is slowly being revealed about US foreign policy authors,

quite frankly, doesn't look any better.

New York, N.Y.: Today we learn that the UN in Iraq was

bombed. The fight on terrorism is a tough one. Please comment on the importance for the

CIA, the FBI and the Defense Department to work as a team rather than "leak"

information to reporters anxious to cover news stories that ultimately embarrasses

employees and agency heads. Doesn't this hurt the fight on terrorism?

Strobe Talbott: Leaks of the kind you describe are of course

harmful. Having been in government myself, I can remember the damage they did to the

national interest. As for Brookings's contribution on the subject of terrorism, we

produced a series of publications, including two books, on short order, but with a lot of

thought behind them, on homeland security in the wake of 9/11. Some of the ideas we

proposed had an influence on the way the Congress and the Executive Branch addressed the

challenge over the past two years.

Washington, D.C.: The Right has developed so many unabashedly

ideological (and partisan) think tanks at both the federal and state level that are

aggressive about translating ideas into policy. Why hasn't the Left done the same? Where

are our Cato, Heritage, AEI, etc.? I know Brookings thinks of itself as centrist, but why

doesn't it work harder at trying to influence policymakers the way the Right does?

Strobe Talbott: We really do work hard at influencing

policymakers -- we just do so in a different way than other outfits do. They push answers

that are rooted in doctrine. We believe -- and find -- that many policymakers, regardless

of their own party affiliation, are more likely to absorb and be influenced by Brookings

analysis precisely because we have no partisan or ideological ax to grind.

New York, N.Y.: Does Brookings give policy advice to other

governments or does it confine itself to advice for U.S. policy?

Strobe Talbott: It doesn't happen too often that foreign

governments as such ask us for advice, but we frequently have visitors here from other

governments who ask us to help them better understand American policy. Washington-based

diplomats -- that is from Embassy Row -- are frequent and numerous participants in our

public events. Quite a few ambassadors come in regularly to consult with our scholars,

sometimes one on one, sometimes at roundtable lunches put on by our Foreign Policy Studies

department. We also have a number of programs in partnership with research organizations

in other countries. Our Center for Northeast Asian Policy Studies does collaborative work

in South Korea, Japan, Russia and China. We do a great deal in Germany, the UK and France,

and we're beginning to develop some partnerships in India as well.

IRmep: Brookings is being modest. As most now know,

the Israeli policy paper, "A Clean Break: A New Strategy for Securing the Realm" was

prepared by U.S. think tank luminaries Richard Perle, Douglas Feith, Meyrav Wurmser, David

Wurmser, and a number of other leading U.S. pundits. Many Americans are now

questioning whether the U.S. is now implementing what is truly a "foreign"

Middle East policy.

Long Beach, Calif.: Considering the number of think tanks, is

there a way to "rate" them, or mention their sponsors, so that people can get a

read on who exactly is paying the bills? How can we know, otherwise?

Strobe Talbott: Here at Brookings, we believe in

"transparency" -- both as a principle of American democracy (and in other

countries as well), and as a principle for the way we operate. You can find everything you

need to know about our funders on our Website (under "About Brookings"), or you

can get us to send you a copy of our annual report. The IRS form 990 is also available at

your request.

IRmep: Brookings is anything but transparent. It

has followed the same lead of most other think tanks in blacking out the names of

contributors that fund more than 2% of total contributions. Brookings and others are

very careful about hiding this information, because if brought to the light of day, it

would reveal unique insights about the interests that shape US policy.

What is public is the level of individual contributor

concentration. Between 1996 and 1999, a handful of donors, five in all, contributed

25% of the $46 million in gifts, grants and contributions to Brookings. Who

were they? What did they want? What caveats and focus did they wish to see in

the policy research funded by their generous contributions? Few outsiders know.

Washington, D.C.: A good book -- 'Think Tanks and Civil

Societies' by James G. McGann & R. Kent Weaver, one who works at Brookings.

Strobe Talbott: Thanks for the plug. I'll pass it along to

Kent, who's a good friend and colleague and helping us think about the future of Brookings

in what is, as your fellow-questioners have pointed out, a constantly changing and very

competitive environment. But it's also, increasingly, a collaborative environment. The

issues facing our country are so numerous and complex and daunting that all of us on Think

Tank Row, whatever our differences, need to find ways of double- and triple-teaming the

tough issues. That's why we partner with AEI and the Urban Institute, just as two of many

examples.

IRmep: The ability to collaborate, and even physically

connect their buildings, also reveals something about America's top tier think tanks: they

have much more in common with each other than they do with multiplicity of interests

across the U.S. The self referential book is a clear example that think tanks,

working alone or in coalition, are largely closed feedback loops.

Strobe Talbott: To everyone who's participated, my thanks for

excellent questions. And to those I didn't get to, my apologies. But keep in touch through

our Website!

IRmep: Most policy research institutes today do not

actually engage in real research, their main function is policy promotion.

Brookings, AEI, WINEP, Hudson, and others have many predefined ideas about where they'd

like to take America, from ideas on environmental issues, to places like Iraq.

However, Americans can become more informed on policy by

seeking out experts with few vested interests: American academics. We invite you to

consider funding IRmep's Network of Targeted

Academics for that reason: think tanks like Brookings are a problem while IRmep is the

cure. |

Sign

up for IRmep's periodic email bulletins!

Sign

up for IRmep's periodic email bulletins! Sign

up for IRmep's periodic email bulletins!

Sign

up for IRmep's periodic email bulletins!