|

Dividends

of Fear:

America's $94 Billion Arab Market Export Loss

Executive Summary

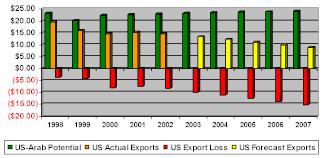

The U.S. share of world merchandise exports to the Arab Middle East slid

from 18% in 1997 to 13% in 2001. This occurred during import demand growth averaging 1%

per year and voracious demand for high value-added capital goods among Arab economies. The

hardest hit U.S. export sectors include civilian aircraft, agriculture, heavy

transportation, as well as telecommunications and industrial equipment. On the demand

side, the broad U.S. export downturn is driven by growing Arab boycotts against U.S.

consumer and industrial goods. These occur as a response to the perceived loss of U.S.

regional foreign policy legitimacy as seen through the eyes of Arab buyers. On the supply

side, the increasing restrictions on Arab business travel to the United States, and

surging U.S. fear, xenophobia and legal campaigns leveled against Arab business are

positioned to accelerate the toll on future trade. The IRMEP estimates that America has

already lost U.S. $31 billion in exports between 1998 and 2002. If the trend continues,

the U.S. stands to lose an additional U.S. $63 billion through 2007 for a ten year export

loss of U.S. $94 billion. (see Exhibit 1)

Exhibit #1

Forecast Actual, Potential and Lost U.S. Exports to Arab Markets 1998-2007

(Source: IRMEP 2003)

This paper examines the actual vs. potential U.S. merchandise exports to Arab

markets by industry category. IRMEP suggests strategies for overcoming export obstacles to

members of the U.S. business community and government. More effective engagement can

reverse U.S. export damage while sowing the seeds of broader U.S. interests across the

region.

I. By the Numbers: Lost U.S. Merchandise Exports

“Are you still smoking American cigarettes?” one Arab asked another beneath a

billboard filled with the imagery of a bloody Israeli military intervention into the

occupied territories. The question calls for the boycott of American consumer goods for

U.S. complicity in supporting Israel, U.S. military interventions, and regional policies

few Arabs feel are just. Questions like this have been asked many times in Arab markets.

Now, the constant and growing pressure to boycott the U.S. has begun to quantifiably

damage American exports. Although overall import demand across Arab Middle East markets is

robust and growing, the U.S. share continues to drop.

Some skeptics point to isolated successes such as the increase in total U.S. exports to

Gulf heavyweight United Arab Emirates (UAE) as proof that the boycott is neither a broad

nor growing phenomenon. However, analysis of recently released Census Bureau Foreign Trade

Division and U.S. Department of Commerce data reveals otherwise. While total UAE imports

grew from U.S. $29.2 billion in 1999 to $35.9 billion in 2002, the U.S. market share

actually decreased from 8.1% in 1999 to 7.4% in 2002. U.S. exports to UAE are suffering as

much as exports to other Arab markets.

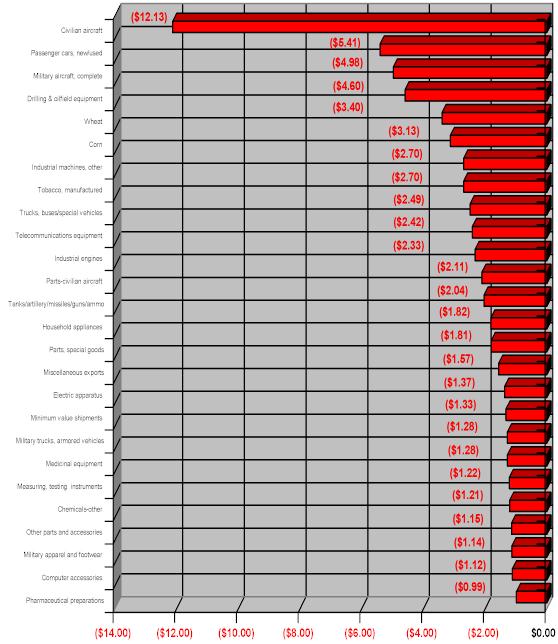

High value-added U.S. industries are among the hardest hit. Between 1998 and 2002 exports

of civilian aircraft represented 13% of total U.S. exports to the region. Aircraft exports

were U.S. $3.9 billion in 1998 and U.S. $1.4 billion in 2002. Although the U.S. export of

aircraft to global markets was experiencing a cyclical downturn of -3.4% over this period,

the mean annual decline in U.S. aircraft exports to the Arab Middle East reached -11.8%.

Other hard-hit industries experiencing damage far beyond normal cyclical demand

fluctuation included industrial machines, transport equipment, telecom equipment, spare

parts and military gear. The trucks, buses and special purpose vehicles category, which

represented 3% of total U.S. exports to the region, was $663 million in 1998 and to $215

million in 2002. The “America Inc.” consumer brand is in danger of extinction in

Arab markets. Branded U.S. consumer goods, de facto subsidiaries of “America

Inc.” such as cigarettes and beverages have suffered massive losses. In March 2003,

Coca-Cola announced it was permanently relocating its Middle East headquarters,

established a decade ago in Bahrain, to Greece as Arab demand for non-U.S. branded colas

surges.

Although the Bush Administration has signaled that a free trade agreement with

preferential tariffs is the new U.S. approach to the region, in reality, tariff barriers

within Arab markets and the U.S. have already been declining steadily.

Tariffs in Egypt declined 3% from 1995 to 1998. Saudi Arabia, while in the midst of a

project to increase domestic production and industrial growth for jobs creation

“Saudization” only saw mild increases in tariffs, amounting to 0.1% between 1994

and 1999. Also, positive regional common external tariffs and trade agreements between

Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) members is improving. (see Exhibit #2)

Exhibit #2

Arab Market and U.S. Mean Tariff Declines

(Source: World Bank and IRMEP 2003)

Country |

Benchmark Years |

Weighted Mean Tariff |

Period Variance |

Average Annual Tariff Declines |

Egypt |

1995 |

16.7% |

|

|

|

1998 |

13.7% |

-3.0% |

-1.00% |

Oman |

1992 |

7.4% |

|

|

|

1997 |

4.7% |

-2.7% |

-0.54% |

Saudi Arabia |

1994 |

10.7% |

|

|

|

1999 |

10.8% |

+0.1% |

+0.02% |

United States |

1989 |

4.1% |

|

|

|

1999 |

2.8% |

-1.3% |

-0.13% |

The U.S.'s largest regional challenge is not tinkering

with tariffs, but rather stimulating waning Arab market demand for U.S. merchandise. Total

Arab market imports (see the end note for countries included in this report) have grown

from U.S. $117.67 billion in 1997 to $119.42 in 2001. If this steady growth rate continues

(and some economists believe it may accelerate), total regional import demand will reach

U.S. $126.6 billion by 2007.

IRMEP believes that a conservative expected mean share of U.S. exports to the region in

1998-2002 should have been 19.05% of the total Arab market rather than the 14.95% actually

achieved. 19.05% is the actual 1998-2002 market weighted mean share of U.S. exports to

non-Arab UNCTAD petroleum exporting category countries that annually import more than U.S.

$1 billion in American merchandise. This benchmark rate of American export penetration

applied to past and future Arab import demand yields U.S. $229.91 billion in 1998-2007

American exports to the region.

If the preceding half-decade's trend continues (four years of export declines for

every year of advances), the U.S. will lose Arab market share at the rate of -7.3% per

year. Analyzed this way, the U.S. has irrecoverably lost U.S. $31 billion in Arab export

opportunities. And while past losses cannot be recouped, $63 billion in losses have yet to

be realized. IRMEP conservatively forecasts total non-cyclical U.S. export losses between

1998 and 2007 will exceed U.S. $94 billion. The most heavily damaged U.S. export

categories are high value-added industries including civilian aircraft, passenger cars,

military aircraft and drilling/oilfield equipment. Affected industry categories also

include agricultural output and many consumer packaged and non-durable goods. (see Exhibit

#3)

Exhibit #3

1998-2007 Forecast U.S. Arab Market Losses (U.S. $Billion) by Export Category

(Source: IRMEP 2003)

The 19.05% benchmark rate is an achievable U.S. total market share

goal. Amidst global oversupply and building deflationary pressures, U.S. industries must

strive to return to their fair share of Arab markets. Within a larger framework of

productive engagement, increased U.S. exports can be a catalyst that solidifies the

realization of broader American interests in the region. However, American industry

associations and leading corporations must begin to confront and roll back a number of

entrenched and narrow interests that actively harm exports.

II. Negative Factors Impacting U.S. Exports

Supply-side obstacles have less of an impact than demand side issues, but will accelerate

the damage to future U.S. exports if left unchecked:

Supply Side Issues

The following two factors have negatively affected U.S. exports to the region:

1. Increased Asian competition: U.S.-Asian competition

across many export categories is heavy. As one Arab industrial buyer mentioned, “my

Asian suppliers can now usually match the U.S. on price and sometimes quality. Before,

there was always a subtle psychological premium to buying American. Now, that premium has

been blown away.”

2. Strong U.S. dollar: Bush administration is beginning

to address the strong U.S. dollar. In the past, the strong dollar made U.S. manufactured

goods prices somewhat less attractive than those of foreign competitors, though not enough

to account for the magnitude of U.S.-Arab market share losses.

Other factors are only beginning to be felt but will accelerate the downturn in the

future:

3. U.S. visa restrictions on Arab business travel:

Total foreign visitors to the United States between 1994 and 2001 increased 6.83%

annually. Arab visitors, represented by Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Jordan and UAE trailed

slightly at 6.75% annual visitor increases. Although 2002 data is not yet publicly

available, anecdotal evidence suggests that Arab visitors in particular have been driven

away as U.S. visa processing requirements begin to treat even longtime international Arab

executives more like “suspects” than “prospects.” As one Gulf State

ambassador recently stated “our elite business people are not going to undergo

fingerprinting just to renew a U.S. visa.”

4. Anti-Arab xenophobia campaigns and damaging political

appointments: Prominent U.S. think tanks continue to produce and evangelize a

large quantity of anti-Arab “research”. These include studies such as David

Wurmser's work on “Battle Cry of Tyranny: Anti-Americanism in Arab

Politics” or Daniel Pipes' books that encourage U.S. fear of Arabs by

propagating an idea that 15% of all Muslims are potential terrorists. Heavy funding for

these types of projects continues to flow, though usually only from a handful of niche

ultra-conservative pro-Israel foundations, individuals, and unsuspecting corporate donors.

5. Plummeting Arab foreign exchange students: The

number of Arab students studying in U.S. universities has plummeted. Their concerns about

personal safety and the financial and privacy costs of onerous U.S. visa application and

student tracking requirements have made European alternatives ever more attractive. Over

the coming decades, Arab business people familiar with U.S. principles and practices will

steadily decline. The current generation of executives will retire and be replaced by

graduates of foreign universities with few insights into or firsthand experience with the

U.S. Also, as new movements dedicated to shutting down U.S. university Arab studies

departments and diverting funding, such as “Campus Watch”, continue to achieve

their objectives, the number of international U.S. executives able to function capably in

the region will also decline.

The Asian trade factor is largely beyond U.S. influence. U.S. officials appear to be

reassessing issues surrounding the strength of the dollar. The damage caused by the other

factors will largely be felt in the future, but can be addressed now. However, the most

important actions the U.S. must now take address and influence demand issues.

Demand Side Issues

America's reputation and credibility in Arab markets has hit a new low point, and

poses the greatest danger to future U.S. exports. The single driver of the growing

preference for non-U.S. imports is negative Arab perceptions about regional U.S. policies.

Recent Bush administration statements about Israeli-Palestinian peace plans and more equal

treatment of regional concerns have been welcomed in Arab markets. However, only tangible

results of changes to U.S. policies will regenerate demand for U.S. exports:

1. Reaction to U.S. Engagement Programs: Positive U.S.

actions such as the U.S. Middle East Partnership Initiative and the recently announced

trade agreement plan are viewed with skepticism due to the minimal levels of U.S. funding

commitment, suspicious timing, low regional relevance and even lower expected impact. U.S.

corporations continue to be targeted in retaliation. A blunt weapon, Arab selection of

alternative suppliers affects many U.S. business interests that have had little first-hand

responsibility for U.S. regional policy. Strong and equitable U.S. actions, as opposed to

weak “vision statements” and public relations campaigns are sorely needed.

2. The Arab Boycott: Israel will continue to be a

regional pariah to Arab consumer markets until the U.S. enforces a just settlement with

the Palestinians. Bush Administration statements wish that “regional hatreds will be

swept away”. Officials have attempted to gain guarantees that the boycotts will be

dropped by participating Arab states, thereby creating a more productive environment for

peace. However the elementary force of Arab outrage at the historical injustices visited

upon Arabs during the creation of Israel lingers on. It is unrealistic to expect or demand

that normal trade and relations commence over the short term between remaining Arab

boycott countries and Israel until root causes of conflict are equitably resolved and

sustained over time.

3. Increasing U.S. Legal Exposures: Actual and planned

lawsuits leveled against Arab corporations and individuals formerly playing a prominent

role in trade are on the rise. Arab traders and investors fear well-funded legal fishing

expeditions searching for any opportunity to “link”, sue and try cases before

highly sympathetic U.S. judges and juries. “Doing business while Arab”

increasingly means fending off the threat of massive U.S. damage claims mounted against

any identifiable pool of assets. This will continue to move many corporate good citizens

and their investments out of the U.S.

4. Judgment of U.S. Fairness and Neutrality: Some Arab

thought leaders will continue to measure many U.S. initiatives by their stated or

perceived benefit to Israel. Arab buyers punish U.S. exporters in a “one brand”

approach toward rejecting U.S. overall policy in the region. Right or wrong, massive

military aid to Israel, U.S. unwillingness to militarily, politically, or financially halt

illegal Israeli settlement expansion, and the U.S. invasion of Iraq are all seen as

actions largely conceived, promoted, and implemented for the benefit of Israel. All

“America Inc.” brands subsequently suffer.

The Bush Administration Trade Proposal

Many aspects of the May 9, 2003 Bush administration plan for a regional free-trade

agreement have been met with surprise in Arab markets. The announced proposal revealed a

lack of understanding about indigenous Arab movements toward freer trade, and regional

market system realities. Key concerns include:

1. Timing: The timing of the Bush announcement has been

questioned. Some Arabs wonder whether it is intended to confront the core issue of

foundering regional demand for U.S. merchandise, or merely focus attention away from

coalition post-war security and infrastructure rebuilding challenges in Iraq.

2. The Boycott: Although many Arab states are already

working toward WTO accession, the Bush admonition that WTO is most important because it

would require Arab markets to drop their boycotts of Israel in order to enter the global

system raises questions. Many Arab governments feel their boycott of Israel is as

justified in principle as the U.S. trade embargo on Cuba. Remaining boycott states are not

making WTO entry adjustments as a bid to favor Israeli exports.

3. Arab Corruption Charges: President Bush slighted

Arab business by trumpeting trade as a way to combat Arab corruption. "By replacing

corruption and self-dealing with free markets and fair laws, the people of the Middle East

will grow in prosperity and freedom," Mr. Bush said in his commencement speech to

1,200 graduates of the University of South Carolina. That this type of prejudicial

language, formerly emanating only from the ranks of fringe neoconservative policy pundits,

has now been adopted by the White House is both troubling and unproductive.

Many Arab business people were perplexed and hurt by charges of self-dealing from a nation

suffering its own corporate governance issues and the aftermath of widespread corruption

on Wall Street. “We know these types of sentiments are all but exclusively for

domestic consumption” stated one Gulf state ambassador to the U.S., “but when

the time comes to make a major purchase, we certainly remember them.”

4. Petroleum Market Realities: With or without a trade

agreement, an important portion of the system will continue to function as a petroleum

market. In this system any U.S. merchandise exports, goods with many substitutes, are paid

for by petroleum exports, goods with no substitutes. Even powerful U.S. players such as

petroleum service, engineering and construction industries protected by their size,

expertise and relationships may face greater market substitution pressures in regional

markets. The June 6, 2003 Saudi cancellation of US $25 billion in regional infrastructure

projects could be only the beginning. Meanwhile, consumer and tech export sectors that

rely on the synthesis of ingenuity and marketing savvy to sell sophisticated products to

“hearts and minds” in Arab consumer and enterprise markets will continue to lose

out even if a falling dollar lowers their prices relative to the competition.

III. Recommendations

U.S. interests can be achieved by nullifying factors damaging market demand. In this

section, we propose concrete steps that individuals in U.S. business and government can

pursue toward restoring U.S. credibility and integrity in the region and ultimately

regenerating Arab demand for U.S. exports.

IRMEP Recommendations to Business

Businesses negatively affected by Arab market demand can take three steps to improve their

export prospects in the short and medium term:

1. Increase the distance between your brand and U.S. policies: Many

U.S. corporations in affected industries have already sought to emphasize the amount of

local Arab market inputs that go into their production, and stress the global nature of

their business.

This positioning alone is not enough to trigger an inflection point in Arab market demand.

Companies marketing to Arab consumer and small to medium size enterprise markets in

particular need to begin sending messages that their brands are part of the solution, not

the problem. The messages can be deeply serious or even light-hearted in tone. Two key

messages that can be integrated into regional publicity and public relations include:

a. “We are working toward peace and justice.” (Serious):

American companies selling to the region can emphasize through charitable contributions

and involvement in Arab relief agencies how they are working toward alleviating

Palestinian suffering and that of other victims of regional conflict. Billboards and

broadcast media positioning consumer brands alongside relief and development service

images can somewhat decouple an American brand from U.S. foreign policy.

b. “We're not so stupid as to blame you for 9/11”

(Humorous, light): Humorous ads depicting the so-called “ugly American”

blaming all Arabs for 9/11 and how the affected company's brands transcend Arab

smear, fear and discrimination can tackle demand issues in a lighter and brand-effective

way.

2. Scrutinize corporate policy research funding: Most

corporate foundations don't consciously fund vitriol and discrimination or otherwise

try to feed the growing Arab xenophobia machine in the U.S. However, many corporations

that do give, particularly to certain Washington D.C. policy think-tanks, may be

contributing to fear and xenophobia campaigns without realizing it. The American

Enterprise Institute, Hudson Institute, Middle East Forum, Washington Institute for Near

East Policy and other neutral sounding policy think-tanks that have promoted highly

questionable and negative Middle East policies are generally very narrowly funded by a

small handful of contributors (See http://www.irmep.org/member_support.htm). However,

corporations in negatively affected industries should nevertheless carefully analyze and

screen their corporate giving programs in order to determine whether they are unknowingly

funding works of little academic merit that harm their own core business interests.

3. Get involved in regional U.S. policy issues that negatively

affect consumer demand: Packaged goods and other corporations in industries that

rely upon consumer or enterprise market goodwill need to get more involved on Capitol

Hill. Misguided and damaging legislation pitched by narrow interests in the U.S. Congress

can create billions of dollars in losses when they do not receive a healthy dose of

attention by affected industries.

IRMEP Recommendations to U.S. Government

Although business interests can work toward creating solutions to U.S.-Arab export

declines, only the U.S. government can take the larger steps to restore U.S. regional

credibility and trade with Arab countries.

1. Enforce an Israeli-Palestinian solution: Many D.C.

think tanks routinely broadcast a common message about US-Arab discord, that “Israel

has nothing to do with it”. They are wrong. Currently, many Arabs expect that the

U.S. will be either unable or unwilling to apply constructive pressure upon Israel toward

achieving the road map for peace proposal, irrespective of any apparent “break

through”. Arab markets are fatalistic in expecting events to emerge over the long

term which will lead to the retention or even expansion of Israeli-occupied territories,

and the complete minimization of Palestinian interests. It is up to the U.S. government to

demonstrate with acts, rather than words, the willingness to force a just solution. This

alone would bolster the “America Inc.” brand.

2. Appoint experienced Arabist regional analysts to key U.S.

policy positions: Most current Bush administration Middle East appointees have

compromising ties and are widely believed to be over-weighted with alumni from pro-Israel

lobbies. The most recent nomination of Daniel Pipes for the United States Institute of

Peace is a case in point. Pipes has made numerous statements such as, "Western

European societies are unprepared for the massive immigration of brown-skinned peoples

cooking strange foods and maintaining different standards of hygiene. All immigrants bring

exotic customs and attitudes, but Muslim customs are more troublesome than most." The

influence of individuals with a long and documented record of racist thinking and their

subsequent policy products is a direct contributor to declining U.S. regional trade and

engagement, and must be reversed. Currently, no high-ranking regionally credible appointee

thought to be an “Arabist” occupies any top policymaking position.

3. Target funding for illegal Israeli settlements: Arab

markets have watched blunt U.S. efforts to trace and stop terrorist financing by rolling

up unregulated Islamic charity networks operating in the U.S. Now, the U.S. Department of

Justice must also publicly roll up U.S. networks that have financed the illegal expansion

of settlements in Israeli occupied Arab lands. The U.S. must indict, arrest, and prosecute

persons and organizations actively flouting U.S. peace initiatives. These include select

religious funding networks and individuals operating in the U.S. such as “Bingo

King” Irving Moskowitz or former Texan and West Bank developer Homer Owen.

Prosecution for the transfer of funds from the U.S. in order to expand illegal Israeli

settlements at the same time the U.S. government has been calling for a settlement freeze

and dismantlement would bolster the U.S. position as an honest broker in the current peace

process.

4. Streamline Arab business and student U.S. visa processes: The

background and activities of 9/11 ringleaders and collaborators are easily distinguishable

from those of longtime international business people and legitimate foreign students

seeking entry into U.S. universities. The U.S. should leverage its new and hard-won

knowledge base about terrorists in order to streamline visa renewal processes for veteran

Arab business people. It must also limit the invasion of privacy and time demands placed

upon low-risk individuals who pose zero threat to homeland security and have the greatest

potential benefits to present and future U.S. trade.

5. Consider the trade and export cost of regional policies:

The administration must begin to calculate the opportunity costs of U.S. policies on

businesses operating in the Middle East. Cynics may claim that no loss is incurred whether

U.S. goods and services are consumed as regional exports, or consumed in military

campaigns, foreign aid, and reconstruction. In fact American taxpayers fund aid and

military interventions, while U.S. business loses billions of dollars in market

opportunities.

The obstacles identified in this report harm exports and produce only one payoff, the

dividends of fear. We must begin to take new approaches that encompass broader American

interests through legitimate pro-engagement policies.

|

Sign

up for IRmep's periodic email bulletins!

Sign

up for IRmep's periodic email bulletins! Sign

up for IRmep's periodic email bulletins!

Sign

up for IRmep's periodic email bulletins!